On Hist Fic Saturday I am delighted

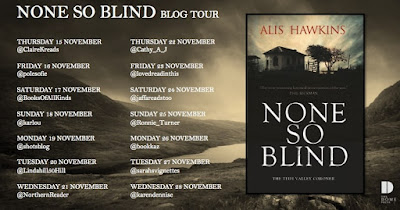

to host today's stop on the None So Blind Blog Tour and to welcome the author, Alis Hawkins

Hi Alis and a very warm welcome to Jaffreadstoo.

Many

thanks for hosting me at Jaffareadstoo, Jo – it’s such a pleasure to be here as

part of None So Blind’s blog tour.

I

write historical crime fiction because I’m fascinated by the nitty gritty of

how people lived in the past. (And I’m talking about the real past, here, not

the past as defined by Crime Writers Association rules. The CWA believes that

any novel set more than thirty years before its publication date counts as

historical which I find more than slightly alarming. How is 1988 suddenly history?

But I digress.)

When

you write historical fiction set well before the bounds of living memory, you

have to be very aware of the constraints on your characters’ attitudes as well

as their actions. You can’t just dress modern humans up in period clothes and move

them about in the past; the people in your fiction have to reflect the actual experiences,

world-view and understanding of their time.

I

find that I’m constantly trying to distinguish between aspects of humanity that

might be considered hard-wired (pesonality and emotional responses) and aspects

that are simply circumstantial (attitudes and beliefs). It’s harder than it

might sound, especially as current research in psychology suggests that very

little is hard wired, that we’re all the product of the effects of our

environment and our world view on our particular genetic makeup.

But

one thing that does seem clear is that certain types of person have always

existed. Warriors, dreamers, carers, tyrants, healers, poets, priests,

peacemakers, disturbers of the peace... These archetypes are fundamentally

human, they simply present themselves in different forms as the centuries go

by.

And

I’d add another to that list, a type that’s of particular interest to the crime

writer. The psychopath.

Though

a certain type of crime fiction has tended to promote the misleading belief

that psychopath = serial killer, I’m interested in fiction that presents a more

nuanced view. Patricia Highsmith’s Tom [The Talented Mr] Ripley, for instance,

is a much more fascinating (and realistic) example of psychopathy; a

superficially charming and engaging young man who slides through life, his path

lubricated by amorality, spontaneity and clever manipulation.

The

Ripleys of the world are both more intriguing and more troubling than the fictional

Broadmoor candidate because they actually exist all around us. If we believe current

estimates, at least one in a hundred people is a psychopath which means that

even the least well-connected amongst us probably knows at least one. And I’m

far more interested in writing about characters we can all recognise than in

creating the kind of serial killing anomaly with whom we are colossally unlikely

ever to come into contact.

Evidently,

many authors feel the same because crime fiction is full of ‘one percent’

psychpaths. Think about it - anybody who takes the time to plan a murder and

carries it out in cold blood must be well on the way to full-blown psychopathy.

Most of us would turn into a gibbering wreck if we’d so much as killed somebody

by accident, or in the heat of the moment; we would, very swiftly, either give

ourselves up or give ourselves away. Not so the cool-headed, pathologically dishonest

psychopath who feels no remorse at removing inconvenient people from their path.

But

why are such manipulative and unfeeling people so popular in fiction? Is it really

just because our fictional detectives need a credible and elusive bad guy to

investigate? Because we’re happy to see them brought to justice at the end of

the book as we finally see what repellent characters they are under their easy

charm?

Perhaps

the real reason is more subtle and more disturbing. Because, if we’re honest,

psychopaths flaunt personality traits that we may find just a little bit attractive.

They demonstrate a hunger for spontaneity and excitement, have an ability to create

and project an utterly convincing persona, show a capacity to act swiftly and

decisively without being weighed down by thoughts of the emotional and moral

consequences, and can lie fluently and persuasively in order to get what they

want. But, of course, we only find these things engaging if we don’t have to

live with them every day; in fiction, we can observe the psychopath at one

remove, safe on the other side of the page.

I’m fairly

sure that one of the characters in None So Blind would meet the psychiatric

threshold for psychopathy. It wasn’t intentional on my part, that’s just the

way they turned out. But, interestingly, I’m not sure that this character would

have become so psychopathic if they hadn’t had the upbringing they did.

Research seems to indicate that individuals are born with the potential for

psychopathy but that environmental factors in childhood flick an epigenetic

switch to bring the full syndrome online.

So,

are psychopaths born or made?

I

prefer to think they’re made; it makes for a much more interesting book (and a

slightly less alarming world). But I’ll let you read None So Blind and decide

for yourself.

|

| The Dome Press 15 November 2018 My thanks to the author and publisher for my copy of the book and the invitation to be part of this blog tour |

West Wales, 1850.

When an old tree root is dug up, the remains of a young woman are found. Harry Probert-Lloyd, a young barrister forced home from London by encroaching blindness, has been dreading this discovery.

He knows exactly whose those bones they are.

Working with his clerk, John Davies, Harry is determined to expose the guilty, but the investigation turns up more questions than answers.

The search for the truth will prove costly. Will Harry and John be the ones to pay the highest price?

Here's what I thought about None So Blind

This well thought out historical

crime story takes us back to Wales in the mid-nineteenth century and introduces

us to Harry-Probert Jones who has returned to his Welsh childhood home after

working as a London barrister. Harry's homecoming is complicated, for all sorts

of reasons, but it is made worse when the remains of a young woman are found

and Harry gets drawn into the investigation.

What then follows is a murder/mystery which threatens to shatter the small Welsh community, exposing secrets

which have been buried for a long time and as Harry gets drawn deeper and

deeper into the mystery he comes to rely heavily another local man, John Davies, for

help as his clerk. The two men make a good partnership and it was fascinating

to watch them peel back the layers of secrets, some of which go back to the

time of the Rebecca Riots which were a series of protests led by local farmers

against the use of toll roads in rural West Wales.

There’s a dark edginess to the

story with lots of twists and turns and I thoroughly enjoyed trying to piece

together the clues alongside Harry and John. Both men have their own secrets

which are gradually revealed as the story progresses and it was fascinating to

see how their personal stories would eventually play out within the wider scheme of the

plot.

The author writes well and it's obvious that a great deal of research has been done which places everything nicely into historical context. I didn't know anything about the Rebecca Riots, so it was particularly interesting to discover more about why the farmers were so angry. I also found the brief Welsh glossary, at the start of the book, really useful.

None So Blind is the first book

in the Teifi Valley Coroner series, so there was a certain amount of setting

the scene and getting to know the central characters who, I’m sure, will

feature strongly in future novels. The conclusion to the story lends itself nicely to a continuation of the series and I look forward to meeting up again with Harry Probert-Jones and John Davies in future stories.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thank you for taking the time to comment - Jaffareadstoo appreciates your interest.